A Hall of Mirrors

- alittlesanctuary

- Feb 25

- 5 min read

What if you were offered hidden information about yourself—insights you’re rarely, if ever, allowed to know?

Would you take that offer?

· Would you take a conversation with a parental or teacher figure who sees things in you you miss in yourself?

· Would you be interested in receiving a personality assessment of yourself written by a top psychologist?

· What if someone were to paint your portrait, and reveal details that bring you both pleasure and disappointment?

· Would you wish to hear a frank conversation that two people are having about you when they didn’t know they were being heard?

· If someone had a crush on you – would you wish to know more about what fantasy idea they had about you? Would it be accurate?

· Similarly if someone had a deep loathing of you – would you wish to know what fantasy idea they had about you? Would that be accurate?

· Would you take a state of the art medical tour of your own body where you are told not just how all your different organ systems work in a generic fashion, but any particular quirks of your own body which give insights into your daily experience, things you find easy, things you find hard etc?

· Would you choose to know a reliable and scientific prediction of the time and cause of your death if you were to die by natural causes?

· Would you wish to hear your eulogy and hear the things people would say about you at your funeral?

· What if you were able to watch video recordings of a hundred people that knew you at different times of your life and how they remembered you, what impression you left on them?

· What if the video recordings were of family members, whether or not they are alive today: grandparents, uncles, cousins etc. and hear what they really thought about you – the good, the bad and the ugly?

Whether you were mostly yesses or mostly nos, what differentiated the information you would have taken from the information you declined?

There are so many ways in which we might be seen – it’s like walking through a hall of mirrors. Each stream of information is a distorted image, not to be taken at face value. But nonetheless each stream of information contains something useful, if weighted correctly.

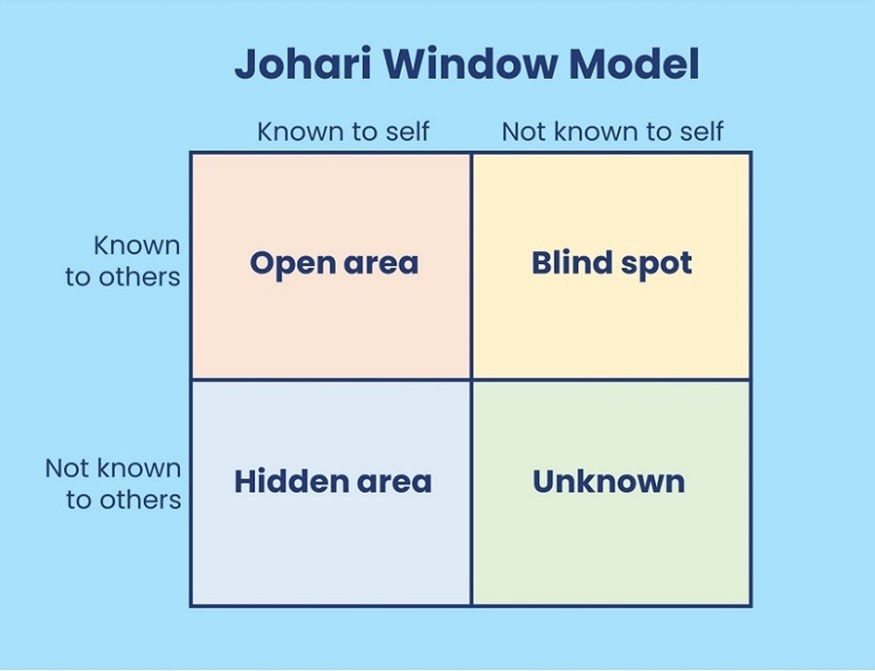

The Johari Window is a psychological model developed by Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham in 1955, and it provides a simple but compelling way of considering the limits of our self-knowledge, and the possibilities for growth. The window is separated into four quadrants:

1. Open Area (Arena) – What is known to both you and others (e.g., your name, visible traits, or behaviours you openly share).

2. Hidden Area (Façade) – What you know about yourself but keep private from others (e.g., personal fears, insecurities, or secrets).

3. Blind Spot – What others see about you that you are unaware of (e.g., unconscious habits, tone of voice, or hidden strengths/weaknesses).

4. Unknown Area – What is unknown to both you and others (e.g., untapped potential, repressed memories, or subconscious drives).

I’m sure each of us could imagine parts of us that sit in the Hidden Area. Perhaps there’ve been times in your life when you’ve been able to share these Hidden parts of you with someone who you discovered you could trust. What I’m mostly concerned about here are the images of us that are currently in our Blind Spot – what others see about you that you are unaware of.

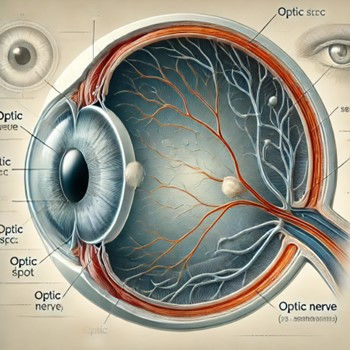

A blind spot, literally, is the point on the retina where the optic nerve exits the eye. This area lacks photoreceptor cells, meaning it cannot detect light, creating a small gap in the visual field.

However, we don’t usually notice this blind spot because:

· The brain fills in the missing information based on surrounding details.

· The other eye compensates, covering the gap in the visual field.

To expand the meaning of the blind spot further here – our basic experience of the world is from our own body looking out. We see others directly (or what we experience as directly), but ourselves indirectly, as reflections in mirrors, photographs, of the feedback of others etc.

To continue the metaphor, there is a self-shaped gap in our visual field, but our brain fills in the missing information based on surrounding details.

The value of feedback from others then is that we derive information that can help fill the gap left by our own blind spot, and thus get a richer, fuller idea of how we are embedded within the world.

As I know well, it isn’t always a comfortable experience receiving feedback.

In my last blog I wrote about an idea I’ve been turning over in my mind which I’ve been calling Piggybacking. It didn’t receive many reactions, which I thought was interesting in and of itself. Several people told me they’d attempted to read it but had found it too intellectual. That was useful to hear and is something I need to work on.

One reader took the time to feed back that ‘It wasn’t a sophisticated idea and it’s been articulated far better in various books and songs.’

Ooof. Thanks.

To be fair to them, it was sandwiched between two nicer comments, but it felt like the most information came in that middle part. And I’m grateful for it, as much as for praise. It is all valuable information.

No-one sees us (or our work) as a complete picture but each perceives a meaningful fragment. Like the hall of mirrors: each view is distorted, but nonetheless conveys something true.

In a very real way, the world knows things about us that we don’t know ourselves. Things we might never get to know and which remain forever in our blind spots.

So actively seeking feedback could be likened to echolocation. We put something out there, and what we get back tells us something not just about the world we are looking into, but how we might stand in that world.

One way to think of this is that when we have a painting to hang on the wall, we place it on the wall to see how well it will fit. We might adjust the positioning - up a bit, down a bit - and consider its proximity to other wall hangings and features. We might even test it out on different walls in different rooms. The point is we're not assessing the quality of the painting as it stands alone but as it sits in a greater frame of reference.

The mirrors in this hall are not reflecting us per se. They’re reflections of us as superimposed into certain worlds. They tell us something about our 'fit' in different worlds; how much we would belong or would be peripheral; how much we would flourish or struggle; the status we might have and the possible roles we might play.

Thus returning back to the original thought experiment, I would always lean towards saying yes to information, because it’s all useful if we know how to hold it lightly; not to be consumed by it, however pleasant or uncomfortable it might be.

Comments